PRELUDE

Print Studio Owner, Publisher, Photographer

Sidney Felsen is the co-founder of Gemini G.E.L., a printmaking studio in Los Angeles that has been operating since 1965. Some of his photographs documenting the artists at work at Gemini are collected in the book The Artist Observed. (December 5, 2018)

CONVERSATION

On building life-long relationships

Photographer and print

studio owner Sidney Felsen

on the origins of Gemini

G.E.L. and how his

relationships with working

artists informed his own

creative work as a

photographer.

What do you tell people your role is at Gemini?

I’m a publisher who has my own production studio. There are many publishers who, say, work with artists and they go to a for-hire printing studio who makes the art for them for a fee. There’s a difference. We’re completely hands on. We invite the artist and then if they agree, they come in. We have an etching studio, a photography studio, and a screen-printing studio. And a Richard Serra studio.

You have space just for Richard Serra?

Richard keeps us so busy. He’s so active in creating. We made him his own studio probably within the last two or three years. Some of the artists we work with—like Richard—are old pros, and they know exactly what they want to do. And some of them have no idea.You show them what an etching is, what it looks like, what it does, a lithograph and a screen print. They decide where they want to go with it, or we guide them. They show us what they want and what they want to accomplish, and then we help them find the process that will work best for them.

I feel that the biggest hurdle that a fine-art print faces is the general public thinks that a print is a reproduction of an existing work of art. They think somebody photographed the thing or a drawing and then just printed that.

Julie Mehretu working on one of the 48 copper plates used in the making of Auguries, 2010

Like it’s a poster or something.

Yeah. A poster. Posters are sold in the gift shop of a museum somewhere, for $50 or $100. We give tours at Gemini at nighttime to organizations that are interested in coming to visit us. The printer stays overnight and sets up a stone or a plate in some form of the matrix, and the people that come in with the tour, we ask them to make some mark on it, some scratching or something like that.

And in some form or other, everybody says the same thing, “I had no idea how involved printmaking is, and now I know why you have to charge these prices.” The tours are good for us because they introduce people to what we’re involved in. It’s very intense.

Printmaking is a pure art form. A printmaker makes the image, they process the plate, they print it. 100% of that print is something that they did. And they take great pride in that, and it’s a very honorable profession. And so they live their lives as printmakers, and that’s what they want to do.

You’ve set up Gemini from the beginning as a collaborative enterprise between artists and printmakers. What is your role in the collaboration?

My job at Gemini is developing relationships with the artists, and I’m the administrative head of the production studios. I think my main job is relationships with the artists. And I love it. They’re great people. I’ve been asked so many times, “Oh, I’ll bet they’re really difficult to work with, prima donnas.” It’s not like that at all. My feelings are that they’re no more demanding on us than they are on themselves. They want a form of perfection. If they didn’t want that, they wouldn’t have gotten where they got to. And I also find that the more accomplished the artists are, probably, the less demanding they are. They know what they want. They know what they want to accomplish. They’ll just tell you, and they’re very straightforward.

When Gemini started, one of my closest friends was a fraternity brother who had become a major practicing attorney in the entertainment industry. One of his major feats was writing these 15-page contracts. I had him write one for me. I thought the artists wanted that. And I presented it to a few artists, and I remember Jasper [Johns] said, “Look, if you’re satisfied with what I’m doing, [and] I’m satisfied with you, we’re gonna work together. And if we’re not, one of [us] is going to leave.” And it’s true. In the past 52 years, I’ve had two contracts that were brought in by two artists and they had two attorneys for this. And there was maybe one or two or three others. So it’s all based on handshakes.

Richard Serra stomping Paintstik through a wire mesh to create a texture, 1999

You started as a CPA, right?

I went to the the University of Southern California, and majored in accounting. I thought I knew I wanted to be an accountant, there was no question about it. I knew that in high school. And I was good at mathematics and simple form. So I graduated and worked for a few accounting firms.

I graduated in 1950, and then probably in 1953, I had a girlfriend who I liked, and I liked her family. At their house, there was art on the walls that looked very strange to me. I didn’t understand why they would like something on the wall that was very abstract.

So anyway, I decided that since they were interested, there must be something there. So I started reading some books about artists. Simple books, really. Then I started going to art galleries to look at art. In probably 1954 or ‘55, I decided I wanted to study painting. I wasn’t going to be an artist, but I just was interested in the actual process of doing it. So I took some painting lessons from an individual person, and I liked that. I got interested, and I started meeting some people, and they said, “Why don’t you go to school?”

In Los Angeles there was a school and it was called Chouinard. It was directed and run by Madame Chouinard, and it was a school that had a split student body. About half were fine art students and the other half were animation students. There was another school of art, Otis. I think that has a campus here, or did have, and then UCLA. So I went to art school for somewhere between 15 and 20 years [on nights and weekends].

So, my life really changed by becoming friendly with the teachers and going to all the galleries. I became turned on to art. I always knew I wasn’t going to be a professional artist, but I definitely was very involved in that whole scene. All my classmates became artists.

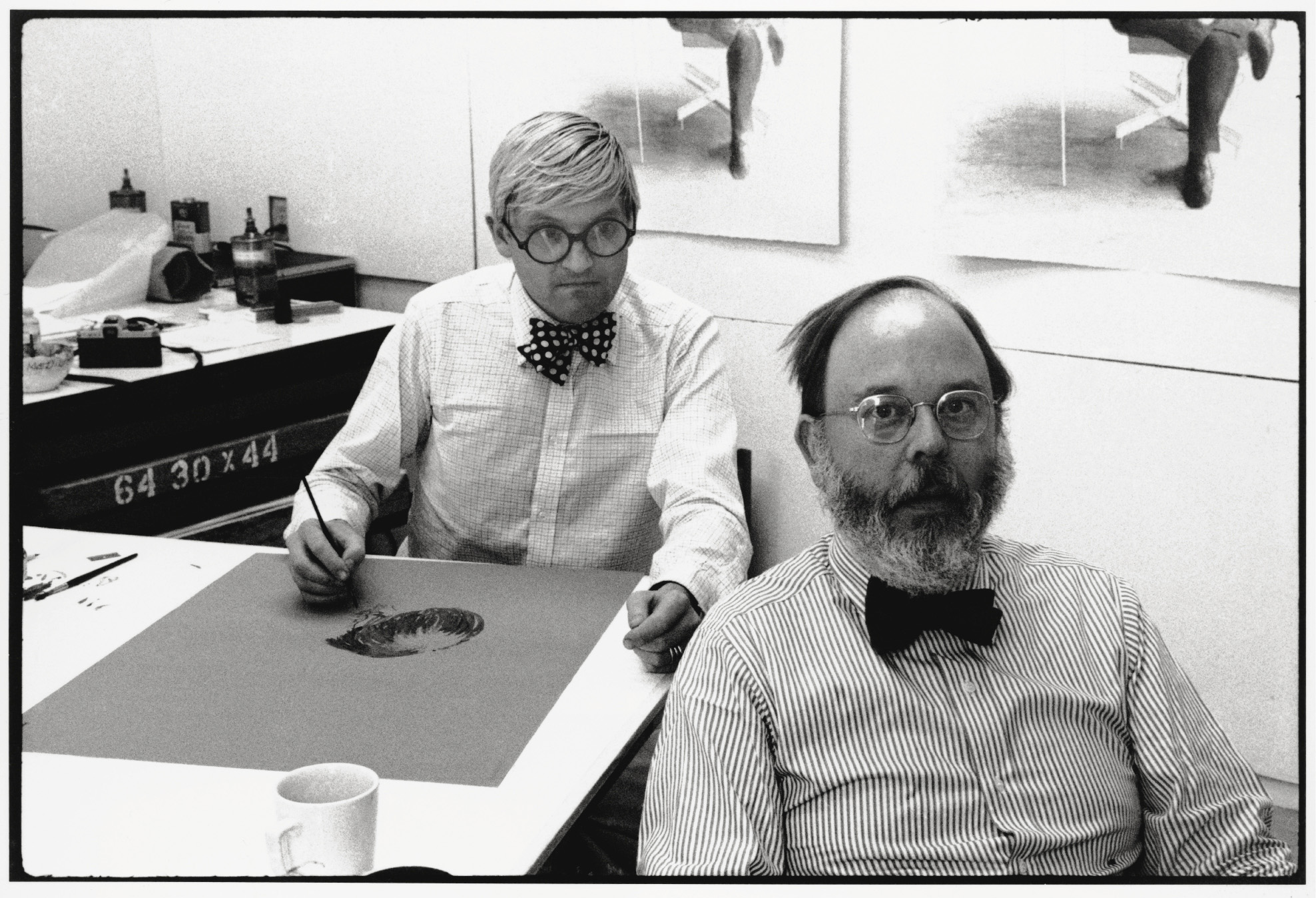

Henry Geldzahler sitting for David Hockney drawing Henry with Bald Patch in the Middle of his Head, 1976

Up until 1965, you’d been involved in art as a hobbyist and an appreciator, but you were still practicing as a CPA, right?

I had an office with a partner. It’d be a small office, and we had relatively small clients. Well, Revlon was one of my clients, but other than that they were all smaller businesses. And that was my business, that was my profession.

When I graduated from USC, I was in a fraternity house, and my closest friend was named Stanley Grenstein. He and I stayed very friendly throughout the years after school. He got married, and his wife was interested in contemporary art, so they started collecting in a very serious way, and built up a major collection.

So I just said to Stanley one day, “They have these workshops in Europe, and the artists make prints. [It would be] interesting if we started one. It’d be fun, and we’d build a collection.” I don’t know what his words were, something to the idea of, “I don’t know anything about it. If you want to do it, I’ll do it with you”.

That must have been a big risk. What did it feel like when you decided to make that investment and make the leap into doing this?

The idea was I’d keep my accounting practice. Stan and I had one question to each other: “I wonder how much you have to keep putting in this thing every year to keep the doors open?” But there was no belief that it would be a successful business; it was more about being in the arts and being around the artists and having fun and building a collection.

Do you think that if it had required more money, you still would’ve done it?

Well, it depends. For those days, it was a fair amount of money to pay. [Gemini printmaker Ken] Tyler had three presses and a pretty good investment in it. But if it had gotten up into, say, twice as much money as we had to put in, I probably wouldn’t have done it. Because I didn’t have the means.

But what happened was, we were an amazing success from day one. Within three years we had six or seven major artists that were working with us, and we were making money. But again, I had my accounting practice, and I was really living off of that, and [Stanley] had a separate business. Stanley and I didn’t take a dime out of the company for probably at least three or four or five years. We had no debts. We had equipment and we paid it all off, 100%.

However, the early feelings were, “This thing can’t continue.” You know, these are the companies that will last three or four years and something will happen. We were probably superstitious about it. But it continued, and so by about the fifth year I turned my accounting practice over to my partner, and I came into Gemini full time. It afforded less than a living salary, but enough to squeeze by. And, you know, it’s now been 53 years.

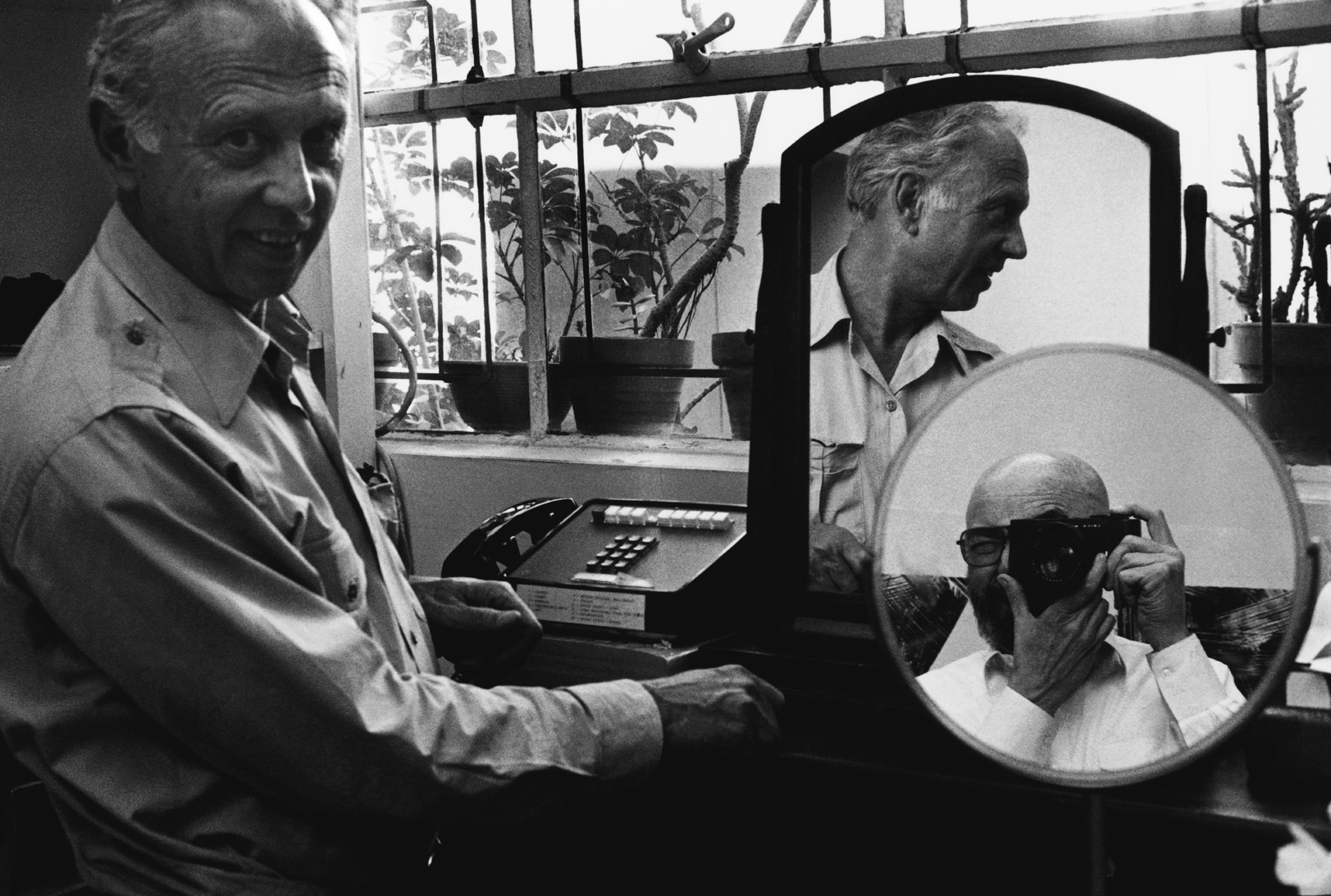

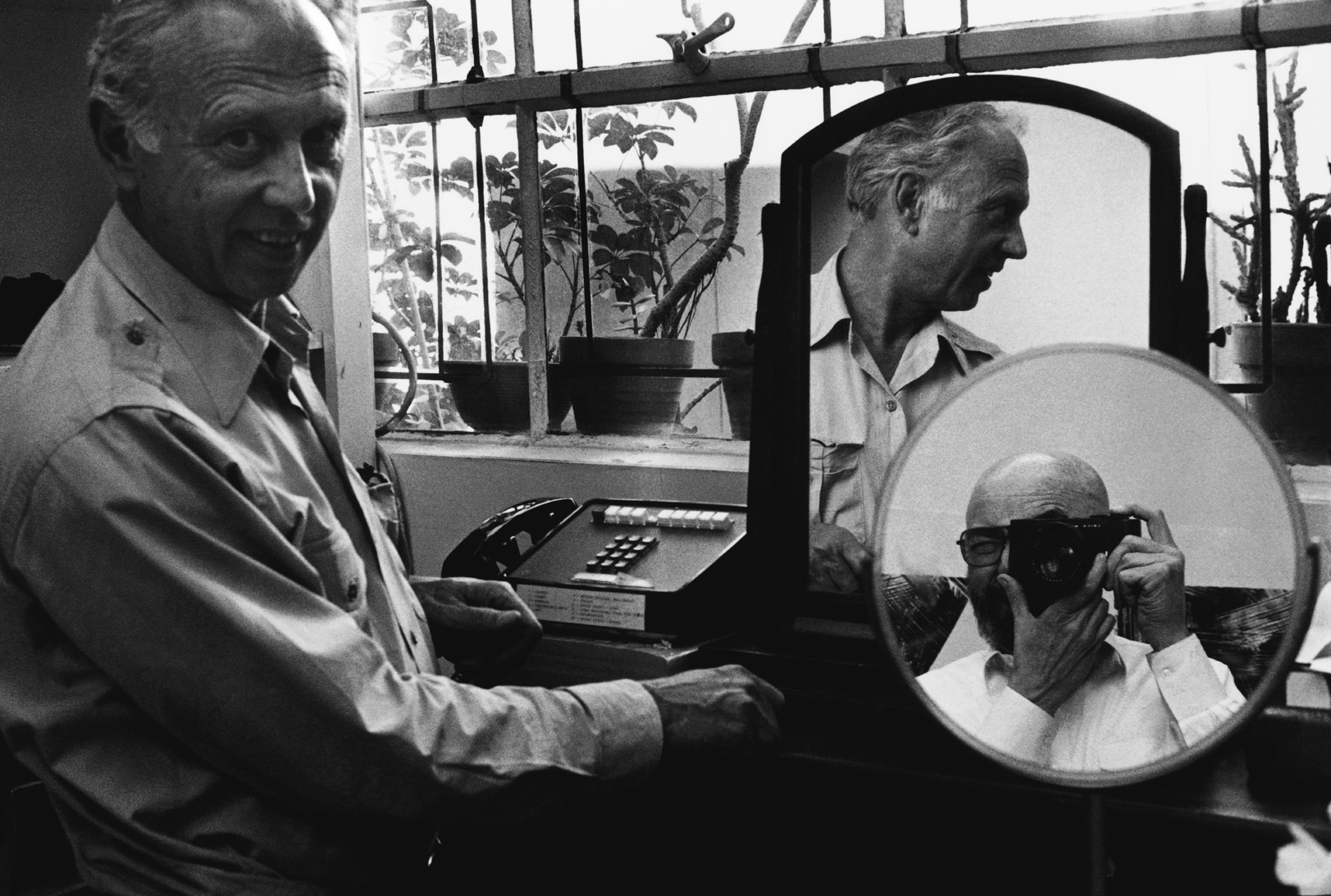

Self Portrait: Sidney B. Felsen, with Ellsworth Kelly (1984)

In the ’60s L.A was outside of the art world mainstream, but you worked and work with some of the most well-known American artists of the last half century. How did you make that happen?

In those days, I didn’t think about this, but every city has a core of what I call regional artists. They’re good, they’re maybe damn good. And their fame and popularity stays in Washington, D.C. or Los Angeles. And then in Los Angeles, there’s Ed Ruscha or John Baldessari or David Hockney, who are international stars, and they’re recognized and appreciated everywhere. We just recently went to an art fair in Chicago. There, you see these artists whose work I’ve seen for 30 or 40 years. But nobody outside of Chicago knows of them. And they’re good.

So here we were in Los Angeles where there were some established artists that were international, but practically none. And the interesting part is that a few of those moved out of Los Angeles. They went and moved to New York, because that’s where you could have a career. But New York is very expensive. Up until recently, Los Angeles was much cheaper. And so it got to the point where artists graduating school became hesitant about going to New York, because they’re hearing about all these high prices.

So I think one of the major effects that Gemini had on the Los Angeles scene early was bringing [Robert] Rauschenberg and [Jasper] Johns and [Roy] Lichtenstein and [Ellsworth] Kelly and [Frank] Stella and [Claes] Oldenburg to Los Angeles. And they began to integrate, as far as friendship, with the Los Angeles artists. All the Los Angeles artists felt the New York scene had its hands out and they couldn’t break through that. I’d say we were influential in sort of breaking through on that attitude about the impenetrable New York scene, or something like that.

You were documenting all of this as a photographer as well.

I think I’ve got somewhere between maybe 50 and 70 thousand photographs of artists working, vacationing together, or spending time together socially at some event or something like that. I’m not judging the quality of the pictures; the good thing about the pictures is they reflect the friendships. Mostly, we’re having lunch, and when we’re getting ready to leave, and I’ll say, “Okay, I’m going to take some pictures.” I’ve had a lot of cases where I sent some pictures to the artist, and they phoned up and said, “I didn’t realize you were taking pictures.” I use a really quiet camera so they don’t hear the shutter. So, it’s part of the whole relationship.

You’re in the room with so many of these artists as they’re creating. And you’re creating as well. You can really see this in your book of photos, The Artist Observed. Do you think of the photos as part of Gemini’s collaborative ethic?

Well, I don’t think of myself as an artist in the room with the artist. I really don’t. In the last year someone changed my perspective on my photographs. Gemini had a show here [in the gallery in Chelsea] in the springtime. It was the first time I’d ever seen a lot of my pictures together. I think I’ve seen 10 or 20 or 30 or something like that. I’ve had a couple of small exhibitions, and it didn’t have that effect. When I looked at the Gemini studio filled with my photos, I thought, “Wow.” I liked what I saw.

I felt good about these pictures I had taken. The show had two different sorts of feelings. One was history and the other was just the emotional feeling of all these people. Gemini’s worked with about 75 artists in the 50 years it’s been going, and if I had to guess, I was probably pretty friendly with more than half of them. It made me feel good. They were my pictures, and they were a success. The photographs, they really touched me.

Robert Rauschenberg drawing onto a limestone for Stoned Moon series, c. 1969

What did you find touching?

Look, you open your doors up and Bob Rauschenberg comes in and works with you. You know, it’s great. When he started working with us, he was about 40 years old. He started when he was about 28 or 29, and Jasper was probably 35, so they were young men. And you know, you work with them, and they’re doing these things, and they’re busy every day, and the years go by. You knew you were working with somebody that was an important artist, a good artist or a major artist. And then probably after 10 years or 15 years, you say, “Wow, this is art history all around you.”

And it starts to take on some meaning where, when I look at these pictures and now, a lot of [the artists] are gone, they’re not even living anymore. You realize that, “Wow, I’ve had better access to so many accomplished artists than maybe anybody else.” They’d come in, and they’d always spend two or three weeks with you, and I’m with them every day. And it’s gone on for years. A lot of these relationships have been going on for 40, 45 years now, or something like that. And so I’ve had this opportunity to photograph so many of them so much. I’m not sure there’s anything else like it. There are professional photographers that have a lot of photographs, but I don’t know. I’m not aware of anybody else who had the kind of opportunity I did.

Some Things

Selected Artists that helped define Gemini G.E.L.

DESIGN INSPIRATION FROM LADY GAGA'S WEBSITE